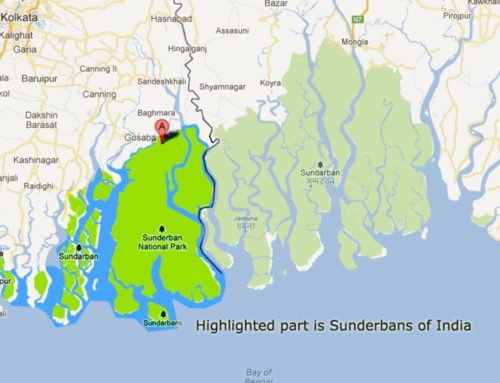

Water and oxygen are the elixir of life which is sustained by the vegetation cover on earth. Barind (alternately called the Varendra Tract in English and Borendro Bhumi in Bengali is the largest Pleistocene era physiographic unit in the Bengal Basin. Barind tract is a physiographic unit located in the north-western part of Bangladesh having gross area of 7,727 sq. km) tract is a place which is fast moving to the point where water crisis might destabilize the natural balance of water, vegetation and the livelihood of people living there for centuries. Home for many disadvantaged ethnic and marginalized communities, Barind area is located in the North-West region of Bangladesh, which is dry and water stressed, facing serious problems of water shortage for agriculture, drinking, and other domestic uses. The situation is worsening due to climate change and the affected areas are expanding, leaving little access to water for drinking and irrigation, posing gigantic threat for the lives and livelihood of the population. Ninety percent of the families living in the Barind area depend on agriculture, animal husbandry and other allied activities for their livelihood. The worst affected are the ethnic communities discriminated disadvantaged population who generally have no official representation in the existing power structure of the local governance. 40.65 percent Union in High Barind tract have been identified as falling into the two most critical categories of very high- and high-water stress areas. These unions experienced a concerning pattern where water levels declined from the previous monsoon to the next, indicating insufficient aquifer recharge.

Water and oxygen are the elixir of life which is sustained by the vegetation cover on earth. Barind (alternately called the Varendra Tract in English and Borendro Bhumi in Bengali is the largest Pleistocene era physiographic unit in the Bengal Basin. Barind tract is a physiographic unit located in the north-western part of Bangladesh having gross area of 7,727 sq. km) tract is a place which is fast moving to the point where water crisis might destabilize the natural balance of water, vegetation and the livelihood of people living there for centuries. Home for many disadvantaged ethnic and marginalized communities, Barind area is located in the North-West region of Bangladesh, which is dry and water stressed, facing serious problems of water shortage for agriculture, drinking, and other domestic uses. The situation is worsening due to climate change and the affected areas are expanding, leaving little access to water for drinking and irrigation, posing gigantic threat for the lives and livelihood of the population. Ninety percent of the families living in the Barind area depend on agriculture, animal husbandry and other allied activities for their livelihood. The worst affected are the ethnic communities discriminated disadvantaged population who generally have no official representation in the existing power structure of the local governance. 40.65 percent Union in High Barind tract have been identified as falling into the two most critical categories of very high- and high-water stress areas. These unions experienced a concerning pattern where water levels declined from the previous monsoon to the next, indicating insufficient aquifer recharge.

Embarking on the Water Act 2013 with the funding support of Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) the Swiss Red Cross (SRC) in association with Development Association for Self-Reliance Communication and Health (DASCOH) Foundation and in collaboration with Water Resource Planning Organisation WARPO implemented the Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) Project in partnership with 39 Union Parishads and 3 Paurashavas in Rajshahi, Chapai Nawabganj and Naogaon districts – the lowest tier of local government that are legally mandated to ensure and regulate water related services. With priority to address the needs of disadvantaged groups the IWRM project covered a total of 106,743 households and 488, 845 population. The project’s prime focus was based on 4R principle e.g., 1. Reduction of over-abstraction and water pollution 2. Reuse of rainwater 3. Recycling water resources 4. Restoring water safety. It was expected that the project will contribute to a paradigm shift to cross-sectoral integrated management of water resources from a sub-sectoral focus on improved water access.

The IWRM Project consists of two complementary components which are

(i) the ‘National Component’ implemented by Water Resources Planning Organization (WARPO) of Ministry of Water Resources (MoWR) and

(ii) the ‘Sub-National Component’ implemented by SRC in association with DASCOH Foundation.

The National Component’s focus was to further develop the national regulatory framework and operationalize the institutional mechanisms foreseen in the Bangladesh Water Act, 2013. The Sub-National Component of IWRM Project was complementing the National IWRM Project by focusing on sub-national government level. Besides supporting national component in developing water rules and organizing and conducting various consultation events intervention strategies applied by the sub-national component were:

- Awareness creation among stakeholders on the importance of IWRM adaptation

- Community based planning, implementation and monitoring through formation and facilitation of WRMCs and their associations.

- Community-led advocacy to UPs in addressing priority needs of meeting the water crisis identified by the WRMCs.

- Comprehensive input to the UP to establish a functional Union IWRM committee and perform their functions assigned by the BWR, 2018 and Union IWRM Guidelines.

The frequency of droughts, cyclones, floods, and other natural calamities across the globe is a stark reminder of the potential threats to human life. It is imperative for us to rise and protect our future. The IWRM project in the Barind area of Bangladesh is playing a crucial role in this endeavour.

Based on its practice generated lessons and learnings SRC and DASCOH believes that the approaches and methodologies have been implemented by the IWRM project have an incredible potential to be replicated nationwide towards promotion of inclusive water governance in a sustainable manner. CLTS Foundation Global-India has undertaken the responsibility of assessing the impact of IWRM project and documenting its implementation process to further enhance the impact of IWRM in Barind area of Bangladesh.

The objective of the study was to assess the impact created by the IWRM project; document the institutional process, strengths and weaknesses and implementation processes applied in the IWRM project. This was also focused to determine the way forward.

The study was carried out between 14th – 24th July 2023. During these 10 days intensive study by a three-member team from CLTS Foundation accompanied by staff from DASCOH Foundation and Swiss Red Cross (SRC) travelled to villages, Union Parishads, Upazilas and Districts of Barind area namely Nagaon, Chapai Nawabganj and Rajshahi. During the entire study, the team members used participatory approaches in eliciting the information from the community members and other stakeholders while visiting various project areas. Additionally, 4 male and 4 female national enumerators were engaged in gathering household data and other allied information through a questionnaire survey. In line with the research ethics, both primary and secondary sources of data including quantitative and qualitative information, opinions and ideas were gathered from relevant stakeholders. Apart from the survey the following participatory tools were used:

- Focused Group Discussions.

- Key Informant Interviews

- Workshops with Union Parishads and Municipalities

- Direct Observations

- Site visits with transect walk and discussions with farmers and water users in the field; and

- Review of videos, and documents.

It was evident from the analysis of data and information, opinions and ideas offered by the beneficiaries at different level that the IWRM project has created significant and lasting impacts. Impact of the IWRM project can be grouped under four broad categories which are institutional impact, social impact, impact on water resource conservation and climate change adaptation.

The impact on climate change cannot be easily measured without rigorous scientific study. Nevertheless, a notable transformation in the vegetation landscape of the project area is evident through the expansion of mango and other orchards. The project has successfully heightened awareness and promoted practices in water resource conservation, resulting in the preservation of billions of litres of groundwater annually. According to the perception of local citizens, the IWRM project’s major impact include the diversification of crop cultivation, improvement of soil texture, and enhancement of biodiversity.

A fairly distinct impact has also been noticed on the livelihood of the people living in the Barind area particularly those who benefitted from the IWRM project. Simultaneously, a negative impact has been noticed in the reduction of opportunity in the seasonal income of the tribal women force due to sharp reduction of more than 75% in the cultivable areas of rice which was replaced by orchard. The tribal women labourer who used to engaged themselves in different stages of rice cultivation (transplanting, weeding, harvesting, thrashing, storage) in large number has been reduced sharply. Although the individual women labour earns more under the orcharding activities, the number getting income opportunity has sharply been dropped as compared to rice cultivation.

The evaluation put forward the approach applied by the IWRM project embody an ample value to be replicated thus deserves more attention and support from the Government of Bangladesh (GoB).

The challenges in achieving a coordinated planning at all level through convergence of targeted interventions of all relevant ministries, departments and agencies engaged in water, agriculture, land and other relevant resource management. Achieving convergence of land and water use plans is also crucial in IWRM still remains a challenge. Another challenge is to have government’s concrete plan and action on the ground. The GoB are yet to officially declare categories of water stress areas and to layout its concrete policy-plans and actions to reduce this serious disaster risk. Although Barind is a home for many ethnic populations, the ownership of most of the land belongs to the elite Bengalis who shifted to orcharding from the traditional rice cultivation. As a result of this shift a few genders negative impact has been noticed on the life of disadvantaged ethnic women. In the context of protection of livelihood land ownership and decision of crop cultivation by landlords often affects the livelihood of marginalized ethnic women which is a new challenge for these women.

Visit to the intervention area of IWRM project

Triangulating ideas and opinions gathered by the study and in consideration of above-stated challenges; the evaluation put across following recommendation for more meaningful way forward:

- Intensify advocacy interventions by developing an advocacy strategic plan to advocate the Barind water issue to higher-level politicians and decision-makers.

- Design and implement special Water Disaster Risk Reduction (WDRR) projects for those Unions and Upazilas under severe threat of water crisis

- Consider a special programme for the promotion of alternative livelihood for disadvantaged ethnic communities.

- Raise stakeholders’ awareness on land use policy and planning

- Introduce participatory water quality monitoring and result sharing

- Continued training and capacity building for the UP Chairmen and Members

- Development of IWRM Training Curriculum

- Intensify interventions related to improve sanitation and waste management

- Encouraging WRMCs to create self-help savings and revolving fund:

- Conservation of surface runoff and rainwater for domestic and irrigation purposes

- Evaluate performance of Rajshahi Divisional WARPO office: Identify performance gaps; and then determine needs to be addressed to make the divisional WARPO office more functional and effective

- Scaling up through horizontal learning and sharing

The IWRM project strategies and methodology applied by WARPO, SRC and DASCOH is highly laudable for its effectiveness and efficiency to promote equitable water governance. However, in terms of sustainability of process it would have been more efficient if the gradual phase-out strategies and framework were an inbuilt component. The project is ending soon but it seems that there remains an ambiguity on the sustainability of the institutionalization process initiated. As an when the project support is withdrawn with the withdrawal of facilitation support by SRC-DASCOH it is likely that the sustainability will suffer a jerk. There is no doubt that institutionalization of IWRM approach require continuation of facilitation input from SRC-DASCOH and WARPO until the established IWRMC at Upazila is ready to perform similar roles. The evaluation recommends WARPO, SRC and DASCOH to develop capacity of Upazila ad Union IWRMCs towards gradual shifting of role to them which are being performed by SRC-DASCOH at the moment. There are examples of self-initiated and voluntary budgetary allocations by several municipalities and UPs for the continuity and sustainability of effort.

DASCOH and SRC could strategize to implement above –stated recommendations by tapping funding from various funding and development agencies to carry on the activities. The major learning from this project could also be disseminated to other areas of Bangladesh and elsewhere through national and regional workshops followed by documentation of the proceedings including case studies of the project areas.

Employment generation, creating a positive impact on nature, and among managing sustainable goals through water resource management, tree plantation, and community-scale workshops, the project is addressing the challenge of water scarcity in a drought-prone area. It not only provides fresh air but also contributes to the improvement of the cost-of-living expenses for the local population. Now, more than ever, it is essential for us to take action and work towards a sustainable and resilient future.

Leave A Comment