Dr. Kamal Kar. Photo credit: CLTS Foundation Global

How can Uttar Pradesh, one of the global epicenters of open defecation, eliminate this scourge through Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS)?

A couple of months ago, I was invited to participate in a major state-level advocacy and training workshop, ‘Good Practices on SBM-Gramin: Brainstorming for achieving ODF Uttar Pradesh’ by the Government of Uttar Pradesh as a resource person in Lucknow on 17th and 18th September 2016.

A few vibrant and enthusiastic District Magistrates (DMs),Chief Development Officers (CDOs) and District Panchayat Raj Officers (DPROs) from eighteen districts of Uttar Pradesh were invited to participate and share their experiences of implementing Swachh Bharat Mission in their respective districts. Their participation in the two-days workshop highlighted some very interesting and intriguing facts and explicitly explained how the young and energetic officials have been fighting the ‘household subsidy monster’ in making villages open defecation free (ODF) in the state of U.P. In India, upfront household level hardware sanitation subsidy has been a feature of sanitation programmes over the past many decades, with the centre contributing 75% and the state providing the remaining 25%. The subsidy amount has been increased more than ten times over in the last couple of decades, with it now standing at Rs. 12,000/ per household.

The CLTS approach was introduced in India in early 2001-2002 in the state of Maharashtra as a pilot in two districts, Ahmednagar and Nanded. The CLTS pilots were successful and subsequently, the approach was introduced in all the 32 districts in the state through series of hands-on training workshops, advocacy, and post-triggering follow-up activities. The success of CLTS in the state brought high-level delegations including ministers and secretaries from the states of Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Rajasthan to the ODF villages in Maharashtra. Interestingly all the state officials who visited the ODF villages were motivated by the power of CLTS in changing the mindsets of the community in stopping open defecation. The then Secretary of Government of India, in a conversation with me, remarked that he was not only very happy but also surprised to see Maharashtra, one of the poorest performing states in the country to emerge as top performing states by adopting CLTS approach.

In 2006 this model was replicated in the state of Himachal Pradesh which brought about a massive transformation in the collective hygiene behaviour across the state. The access to sanitation of Himachal Pradesh shot up from 41% in 2003 to 84% in 2007. Presently, Himachal Pradesh has successfully achieved total rural sanitation coverage of 100 percent in the state, with all 12 districts in the state being both, declared as well as verified as ODF. What was critical to the success of CLTS in these two cases (pilot project in Maharashtra and state wide scaling up in Himachal Pradesh) was the leadership of two senior IAS officers, Mr. BC Khatua, the then Principal Secretary, Water Supply and Sanitation Department, Government of Maharashtra and Mr. Deepak Sanan, the then Secretary of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj, and currently Additional Chief Secretary, Government of Himachal Pradesh, who spearheaded the initiatives in their states respectively. These officials were convinced about the ability of CLTS to initiate collective action towards open defecation without waiting for any outside subsidy or dole. The state level CLTS champions realized that household hardware subsidy was blocking the smooth transition of collective local action as households were allured to grab free government subsidy or material without the necessary motivation to change open defecation behaviour. Even those who could afford to build their own toilets without waiting for outside help didn’t do so. Both the senior officers understood that the roll out of CLTS was only possible if an essential enabling environment to empower local communities without any terms dictated by outsiders was ensured. Community empowerment for roll out of CLTS was not possible because of the top-down, prescriptive, hardware subsidy model existed. These officials at the state level challenged the existing situation and did their best to eliminate household hardware subsidy model ensuring right enabling environment through the issuance of government orders and policy adjustment through cabinet approval and assembly legislation. The government of Himachal Pradesh adopted a policy of no subsidies for household toilets backed by appropriate capacity building initiatives to enable roll-out in campaign mode.This brought about a sea change in the collective hygiene behavior in rural communities of Himachal Pradesh. The triggering exercises of CLTS became meaningful and mobilized communities who invested in local resources to build toilets and stop open defecation(OD) without waiting for any help from outside.

Unfortunately this example of ensuring enabling environment through appropriate policy change was not replicated in any other state in the country and the individual household hardware subsidy continued to be the prevalent policy under ‘Total Sanitation Campaign (TSC)’ in 1999 as well as the ‘Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan (NBA)’ in 2000 to the present ‘Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM)’ in 2014.

Government gives Sanitation the Top Priority: ‘Special Boost for Sanitation in India’

With SBM, sanitation received a renewed thrust and focus in India, making it one of the top four national priorities. Though there is a larger thrust on community mobilization and the need for behaviour change in SBM ever seen before in India, the provision of subsidy is still the guiding framework of all interventions under SBM. The use of the CLTS approach in SBM has been watered down to mere use of triggering tools to generate a need for toilets among community members, after which those eligible are given the sanctioned amount to build toilets. Therefore the focus has continued to remain on acquiring toilets as an individual asset, rather than inspiring collective behaviour change for better sanitation (involving the so-called eligible and not eligible) which is a public good and therefore the responsibility of every single individual in the community. An open defecation free environment guided by shared values, community solidarity and collective action from the community is what sustains this behaviour change as well. With the provision of outside financial assistance, firstly sanitation is externally motivated, seen as someone else’s need and not one’s own and hence not internalized and prioritized by the people. Secondly, when the subsidy is given only to some (those below Poverty line who have not received the same in earlier sanitation programmes) and not the others, there is no scope for collective action as the community gets fragmented. The result as we’ve seen through the many decades and different sanitation programmes in India, is a situation where communities have toilets, but either do not use it or it is used only by some members of the family while others continue to defecate in the open.

With SBM, sanitation received a renewed thrust and focus in India, making it one of the top four national priorities. Though there is a larger thrust on community mobilization and the need for behaviour change in SBM ever seen before in India, the provision of subsidy is still the guiding framework of all interventions under SBM. The use of the CLTS approach in SBM has been watered down to mere use of triggering tools to generate a need for toilets among community members, after which those eligible are given the sanctioned amount to build toilets. Therefore the focus has continued to remain on acquiring toilets as an individual asset, rather than inspiring collective behaviour change for better sanitation (involving the so-called eligible and not eligible) which is a public good and therefore the responsibility of every single individual in the community. An open defecation free environment guided by shared values, community solidarity and collective action from the community is what sustains this behaviour change as well. With the provision of outside financial assistance, firstly sanitation is externally motivated, seen as someone else’s need and not one’s own and hence not internalized and prioritized by the people. Secondly, when the subsidy is given only to some (those below Poverty line who have not received the same in earlier sanitation programmes) and not the others, there is no scope for collective action as the community gets fragmented. The result as we’ve seen through the many decades and different sanitation programmes in India, is a situation where communities have toilets, but either do not use it or it is used only by some members of the family while others continue to defecate in the open.

Photo source: BBC

Within this policy framework and existing reality, states are trying various innovative ways to achieve their targets and meet the national goal of an ODF India by 2019. This workshop brought to light the techniques being used by some of the administrative officials in Uttar Pradesh.

What was different about this Uttar Pradesh workshop?

The recent two-days workshop in Uttar Pradesh brought to light the experiences and reflections of young district level officers on overcoming the subsidy monster and continuing to motivate local initiatives of the people for stopping OD, as a sincere and desperate move to achieve sustainable results.This was indeed an eye opener as these enthusiastic DMs, CDOs and DPROs from 18 districts of Uttar Pradesh shared how the enormous amount of their energy, resources and time was being spent only to overcome the barrier of subsidy, which is blocking the spontaneous collective community action to end OD unleashed through the triggering of CLTS.

Uttar Pradesh: One of the Global Epicenters of the Practice of Open Defecation

Photo source: Indian Express

Uttar Pradesh is the most populous state in India and also one of the top states affected by the scourge of open defecation. According to Census 2011, 78.2% of rural population in Uttar Pradesh defecate in the open. This makes Uttar Pradesh home to the largest number of open defecators in India, a country which contributes to 60% of the open defecation taking place in the world. In accordance to the BLS (Base Line Survey) conducted in 2012 by the Directorate of SBM (Gramin) of U.P, the percentage of households not having toilets is 64.76%. The sanitation coverage of Uttar Pradesh post-BLS in 2012 is 44.13% as on 31st March 2016. After the baseline survey, there is only 2.06% increase in construction and accessibility of sanitation facilities in the state. Uttar Pradesh felt an immediate need to implement CLTS approach for inculcating and empowering behavioral changes in the communities.

Reflections by the DMs, CDOs, and DPROs of Uttar Pradesh on innovative approaches being implemented

In the manner that triggering is being done currently, the triggered communities seem divided. While some of them realize the need to stop OD urgently, the entire community is unable to come together to take collective action due to the divisive nature of eligibility to receive subsidy set by the government. Those given subsidies build toilets but all of them don’t necessarily use the toilets and continue practicing OD. Those not given a subsidy continue to wait for it from the government and in the meanwhile continue OD. With some people continuing to defecate in the open, those using toilets continue being at the risk of contamination. As a result, most communities could not move spontaneously towards achieving ODF status. The community members understood and appreciated the CLTS approach but were allured by the government supported subsidy model.

In the manner that triggering is being done currently, the triggered communities seem divided. While some of them realize the need to stop OD urgently, the entire community is unable to come together to take collective action due to the divisive nature of eligibility to receive subsidy set by the government. Those given subsidies build toilets but all of them don’t necessarily use the toilets and continue practicing OD. Those not given a subsidy continue to wait for it from the government and in the meanwhile continue OD. With some people continuing to defecate in the open, those using toilets continue being at the risk of contamination. As a result, most communities could not move spontaneously towards achieving ODF status. The community members understood and appreciated the CLTS approach but were allured by the government supported subsidy model.

A few senior district level officers firmly believe that it is essential to create self-empowered communities who will enable ODF environments for themselves through their own innovative collective community initiatives. These officials introduced various innovative models in different districts of Uttar Pradesh to overcome the ceaseless dependence of community members on mere subsidies. Their prime focus has been to reduce the emphasis on the importance of subsidy and in this process, they are creating an enabling environment in the communities for continuing with consistent collective local actions that will help achieve ODF. But it has been extremely challenging to mobilize collective local action of the communities because of the traditional thinking of the community members that improvement in sanitation is possible only when it is externally funded.

Sincere and dedicated efforts are being made by these administrative officials to divert the attention from subsidy towards self-realization, collective local action, and social solidarity for ensuring access to basic sanitation to the community members. In this regard, the CDO, Bijnor and his team undertook a baseline survey, after which they triggered the CLTS process which resulted in local innovations in terms of developing ‘Compressed Demand’ that led to ‘Compressed Subsidy’. Through this process, the district team in Bijnor was able to ensure that the entire demand for toilets in a particular community was met with the amount of money available in total for that community, without making individual household allocations. This is another form of community solidarity as this shows that some families were ready to forego a part of the subsidy amount to enable other households to avail toilets as well. In this way, diverse set of people including people with disabilities, widows, senior citizens etc. were brought under the eligibility criteria.

Pride and Dignity were used as triggers during the introduction of CLTS approach in the community. Stopping open defecation was linked with issues of dignity and pride. Toilets were termed as ‘Izzat Ghar’(Dignity Home) and the empowered community members proactively used local and other available materials to develop low cost and appropriate toilets as they sensed the urgency of stopping the practice of OD.

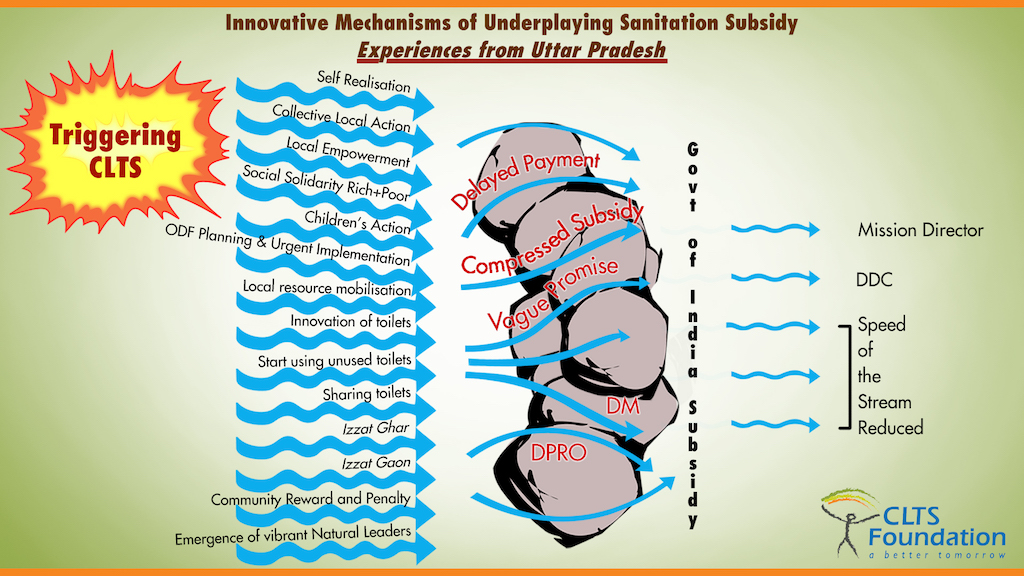

Another innovation tried out in some villages in Bijnor was to offer the subsidy amount as community-based rewards after the achievement of ODF in the community. In this case, the amount would be used for community goods such as roads, schools, water facilities etc. One of the most cherished outcomes of CLTS is shared responsibilities. It happens when most of the community members are mobilized and take actions collectively for the larger good. CLTS also results in the emergence of Natural Leaders (NLs) who play a more active role than the rest of the community in taking the community towards ODF. Some villages in U.P reported peer pressure as another tool for stopping OD. Once triggered the communities come together to stop any defaulter from defecating outside. Those who do are compelled to pay a fine to the Gram Panchayat. All these innovative approaches have to an extent been able to challenge the blockage caused by subsidies and have produced the desired outcome. Below mentioned is an info-graphical depiction of the innovative approaches:

Still, a lot needs to be done in terms of transforming the institutional attitude in thinking, establishing effective collaborations and mainstreaming the approach within the government. We need to create an ambitious yet realistic goal for ensuring successful elimination of OD in India. It is time to trust the power of social solidarity of the local communities and have faith in their abilities to change by encouraging innovations in accordance with the local situations. Rather than viewing subsidized and prescriptive toilet construction as the only solution, community-led approaches have the inherent potential to bring about rapid and long-lasting transformational change.

It would be a national shame if 80% or more of the districts of our country are being declared ODF by the government when they are not so in reality. In other words, the present statistics of child mortality, the incidence of diarrhea, malnutrition and stunting as a health outcome must coincide with such ambitious declaration.

Dr. Kamal Kar is Chairman, CLTS Foundation Global. He is the recipient of Sarphati Lifetime Achievement in Sanitation Award 2015 at Amesterdam.

Leave A Comment